The Times of Israel

By Raphael Ahren

June 28, 2019

I came to Bahrain to cover an economic peace conference, and ended up discovering a small but unique local Jewish community

MANAMA, Bahrain — “They may not make peace in Bahrain, but they made a minyan in Bahrain,” David Makovsky, a DC-based think tanker specializing on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, said Wednesday, as he was taking off his prayer shawl and phylacteries.

We had just concluded the first morning service held in this Gulf nation’s only Jewish house of worship in more than 70 years. Makovsky was sitting in the row in front of Jason Greenblatt, US President Donald Trump’s Middle East envoy, who had come to Bahrain to present the first part of the administration’s peace proposal.

“Participating in shacharit, the morning prayer service, today in a synagogue in Bahrain was very special to me,” Greenblatt told me later on Wednesday. “It was a great example of what can be and should be in this region.”

Just 24 hours earlier, nobody would have dreamed of organizing a minyan — the quorum of 10 men required for a full Orthodox Jewish service — in this Muslim-Arab nation, least of all myself.

It was only when I spotted at least five rabbis as I strolled around the site of the US-led economic peace workshop in Manama this week that I thought it might just be possible.

But first let’s take a step back.

I had tried to arrange a visit to the city’s synagogue for weeks ahead of my trip to Manama for the US-led economic workshop, but the local Jewish community was initially hesitant to open its doors to Israeli journalists. Aware of the acute sensitivity of being a Jew in a Muslim country that does not have formal relations with Israel, I sent several messages, through different channels, to community leaders asking for a private visit, to no avail.

On Tuesday afternoon, my colleague Barak Ravid from Channel 13 suddenly announced to the small contingent of Israeli reporters in Manama that the community had apparently received the green light from the Bahraini authorities, and that we would be given a tour of the synagogue.

We were told to come to an unmarked building on the city’s small Sasaah Avenue at 4 p.m., where Bahraini-Jewish diplomat Houda Nonoo would take us inside and show us around.

A White House official had asked us to attend a meeting at that time at the conference venue, but we insisted it be moved, since we couldn’t pass up the opportunity to visit the shul. It’s not every day that the powers that be in an Arab monarchy grant special permission to Israelis to visit a Jewish house of worship.

I got into a cab and showed the driver the synagogue’s location on a map. He nodded knowingly, but it turned out he had no clue how to get there, and at some point asked me to leave the vehicle and attempt to find the place by myself.

So I went shul-hunting on the busy streets of Manama, in the burning afternoon sun. It was about 45 degrees Celsius (113 Fahrenheit), and I was wearing a suit and tie in anticipation of the White House meeting and the opening session of the peace conference.

A quarter of an hour and probably two liters of sweat later, I finally managed to find the synagogue — an unassuming building that you would never guess is a Jewish house of worship.

When we asked the employees at the hair salon next door what they thought the building was, they said it was some sort of mosque, but that, oddly, “We never see anybody going inside.”

Well, they were right about the second point. The synagogue is closed all year round, even on Passover and the High Holy Days, opening only on very rare occasions. For instance, the 2016 Hanukkah celebration in Bahrain, which made international headlines, was not held in the synagogue.

Jews, mostly of Iraqi origin, have been living in Bahrain since the 1880s, which is why the country claims to be home to the Gulf’s only indigenous Jewish community. (For the last decade there has been an active congregation in Dubai, but it consists exclusively of expatriates.)

In the early 1900s, the Bahrain community established a relatively large cemetery, which is still in use today, but more about that later.

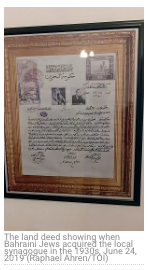

The Sasaah Avenue shul was founded in the 1930s. A framed facsimile of the land deed hangs right next to the Aron Hakodesh, the holy ark. (There is no Torah scroll, so a large menorah was placed inside the ark.)

In its heyday, the community numbered some 1,500 members. But in 1947, in the wake of the United Nations resolution proposing the creation of a Jewish state in Mandate Palestine, the synagogue was ransacked — though nobody was killed — and the community started to dwindle.

The shul was renovated in the late 1990s, but today there are only some 34 Jews left in Bahrain.

Despite its numerical smallness, the community punches above its weight, in terms of societal standing.

Nancy Khedouri, for instance, has been a member of the Shura Council, Bahrain’s parliament, since 2013, and currently serves as deputy chairperson of the Foreign Affairs, Defense and National Security Committee. She has written a book about Bahrain’s Jewish community, entitled “From Our Beginning to Present Day.”

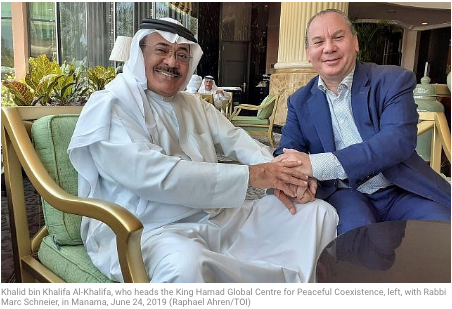

Bahraini Jews are proud of their heritage, and the government in Manama is making great efforts to stress its history of religious tolerance. It also wants to actively promote the local Jewish community, according to Khalid bin Khalifa Al-Khalifa, who heads the King Hamad Global Centre for Peaceful Coexistence in Manama.

“We need a rabbi for the synagogue, a full-time, resident rabbi, so that the Jews can practice their religion,” he told me Tuesday in an exclusive interview.

Nonoo, the diplomat who greeted us this week at the synagogue, served as the kingdom’s ambassador in Washington from 2008 to 2013, and still works at the Foreign Ministry in Manama.

“We need to encourage the young Jews, those who live abroad, to come back and live in Bahrain again,” he added. “It’s very important for us to preserve the Jewish community, because it’s part of the structure of the country.”

Khalifa, a member of the royal family who has been described as the country’s de-facto religion minister, also envisions kosher restaurants in Manama. A thriving Jewish community “is very important for our society,” he said. “Otherwise, you cannot have a country, really, when a piece of it is missing — Jews, Hindus, Christians or whatever. So really we have to preserve them all.”

Bahrain is indeed special in that it has long been tolerant of all religions. The capital’s Hindu temple was built 200 years ago; Christian institutions started opening here in 1893.

Five of the six Gulf states have recently opened or are planning to open interfaith centers, but only the one in Bahrain is “an expression of what is already very much a part of the fabric of the society,” said New York-based Rabbi Marc Schneier, who last year was appointed a “special adviser” to the King Hamad Global Centre for Peaceful Coexistence.

“You don’t need the center to set a new standard,” he said, sitting next to Khalifa in the lobby of Manama’s Ritz Carlton Hotel. “Here in Bahrain, [religious tolerance] has been the standard for hundreds of years. This is where Bahrain is so unique.”

Khalifa, a soft-spoken man in his fifties, said he remembers members of the prominent Jewish-Bahraini Ezra family sharing meals in his home when he was a child.

“Since I was born, we lived in the center of Manama with some Jews around us,” he said.

“Generations after generation, they were living among us. We were celebrating their holy days, and they were also joining us for our holy days. We were living in harmony, without any interference from anybody, and with the utmost respect. That’s how we were living, and that’s how we want our children to live.”

For the time being, however, there is no public Jewish life to speak of in Bahrain. That’s why I was so thrilled when Nonoo allowed us reporters to enter her community’s synagogue on Tuesday. I am not a particularly spiritual person, but as my colleagues filmed and took notes and prepared their reports about our rare visit, I felt the need to utter at least a short prayer and recite a chapter from Psalms.

Two hours later, I was at the Four Seasons Hotel for the opening session of the Peace to Prosperity workshop. After the speeches, we were invited to a gala dinner, during which I chatted with some of the Jewish delegates. But my mind was still in the defunct shul, and it suddenly dawned on me that we could probably organize a minyan there the following morning.

There are a handful of Orthodox rabbis here who would surely jump at the opportunity, I reasoned, and if you add to that the three observant Israeli reporters and perhaps the religious members of the US delegation, it should work.

Nonoo told me she could probably open the synagogue if we indeed managed to get a minyan together. I immediately walked up to Greenblatt, the senior White House official. He was interested, and said he may even bring an aide or two.

Then I approached a few Israeli businessmen and other (not necessarily observant) Jews, some of whom, to my delight, were thrilled at the prospect of attending morning services in Bahrain. I wasn’t certain that everyone would actually show up the next morning — we set the time for 8:30 — but I told Nonoo that I was fairly certain we’d have 10 men.

When I arrived at the shul at around 8:15, it was already unbearably hot, and Nonoo was busy trying to get the air conditioner to work. After struggling with the not-state-of-the-art AC, which hadn’t been used for a long time, we walked to a nearby convenience store and bought 20 bottles of cold water, lest worshipers dehydrate and faint in the Bahraini heat.

At around 8:40, people started arriving, and a few minutes later, we had 15 men, including three North American rabbis, three US administration officials, and three Israeli journalists, ready to pray.

After the service ended, the men spontaneously joined hands and danced in a circle, singing Am Yisrael Chai, “the people of Israel live.” One worshiper remarked that it had probably been a long time since Torah was studied there, and delivered a few remarks on the weekly portion.

“Where’s the kiddush?” someone joked. “When’s mincha?” somebody else piped in, using the Hebrew term for the Jewish afternoon prayer.

“It’s a historic moment. For the first time in my life, I saw a prayer service with a minyan in my synagogue,” Nonoo told me afterwards, as most people had already made their way to the Four Seasons for the workshop.

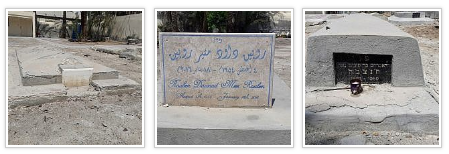

I was supposed to cover it as well, but I really wanted to see Manama’s Jewish cemetery. Very few non-Bahrainis have had the privilege of visiting it, but Nonoo, whose father, grandfather and uncle are buried there, graciously offered to drive me and a colleague there.

“The Jewish cemetery here in Manama is located right next to the Christian and the Muslim one,” Nonoo told us. “It’s symbolic, isn’t it? In Bahrain we all live together, and when we die we are together.”

She parked her black Mercedes outside the barb-wired cemetery walls, took out a key and opened its heavy blue gates. As we walked around the site in the blistering heat, we saw many graves from the pre-1947 period, which are all unmarked, and some of local Jews who died recently.

Whenever someone passes away, the community makes sure to arrange for a minyan to be present at the cemetery so the traditional kaddish mourner’s prayer can be said, she explained. So while the minyan in shul was special, at the cemetery it is commonplace.

Following Jewish tradition, we placed small stones on some of the graves, and recited a chapter of Psalms, before we, too, finally headed to the Four Seasons.

As we entered the hotel, where the workshop was already in full swing, my colleague asked me why I was so moved by the fact that we had managed to organize a minyan in the local shul earlier that day.

“Do you really want Jews to live in Bahrain?” he asked me, implying that the State of Israel, and not some tiny island in the Gulf, is our people’s national homeland.

“I believe it’s everybody’s choice where to live. But that’s not the point,” I replied. “I want Jews to be physically safe and able to openly practice their religion, wherever they may be. And by organizing a minyan and having people sing Am Yisrael Chai, we showed that it’s possible — even here in Bahrain.”

Copyright © 2025 Foundation For Ethnic Understanding. All rights reserved. | Privacy Policy