Patterns of Thought: Britain, France, the US, and Hungary have seen upticks in anti-Jewish invective and assaults in recent years. The resurgence of overt anti-Semitism stems from both an awakening of repressed prejudice and a byproduct of anti-Zionism.

By: Harry Bruinius and Sara Miller Llana

Staff writers

April 11, 2018 NEW YORK; and BUDAPEST, Hungary — There were many reasons the murder of Mireille Knoll in Paris last month reverberated so deeply throughout Europe.

As a little girl, Ms. Knoll barely escaped the ovens of Auschwitz, slipping through the notorious roundup of Paris Jews in 1942 with her mother. But last month, two men, one allegedly crying “Allahu Akbar,” entered Ms. Knoll’s apartment and stabbed her to death, and Paris authorities say it was because she was a Jew.

It was in many ways a complicated local crime. But the raw pathos of the story sent a jolt through many in France and other Western nations, touching as it did on the horrors of Europe’s anti-Semitic past while laying bare one of its deepest current fears.

The story of this Holocaust survivor, however, murdered in her own home by her Muslim neighbor, authorities say, has also magnified an already unsettling rise in anti-Semitism throughout Europe and the United States.

On the one hand, in countries like France and Germany, growing Muslim populations have indeed added new layers to Europe’s long history of anti-Semitic violence, scholars say. Working class immigrants and refugees have brought their own animus toward Jewish people and the state of Israel, and in some communities radical young men have expressed this animus in violence.

Yet even more troubling, many scholars say, is the brazen reemergence of something more ancient, and long woven into the history of Christian Europe: the Jew as an icon of the dangerous “other,” a stubborn, willful rebel in the midst of a sacred order.

‘No longer clandestine or private’

“Anti-Semitism has never vanished in Europe or the US,” says Thomas Kühne, director of the Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Clark University in Worcester, Mass. Indeed, before World War II, anti-Semitic sentiments were both genteel and respectable, even in places like Britain and the United States.

Only after the horrors of the Holocaust did this begin to change. And in many ways, many of the globe’s post-war institutions, including the United Nations and its Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Common Market and other trade agreements, and eventually even the European Union, were built to prevent events like World War II and the Holocaust from ever happening again. Having lost its credibility, anti-Semitism was pushed to the margins.

“Maybe you would still be an anti-Semite, but you would never admit it in public,” says Professor Kühne, noting that about 30 percent of most Western populations have maintained anti-Semitic views over the past 50 years. “The difference now is that not only has this share of the population been increasing, what I find even more important is that it is no longer clandestine or private,” continues Kühne. “That is the huge difference.”

Today, far-right political parties all over Europe have been finding success breaking post-war taboos, playing on anti-Jewish stereotypes, many borrowed from the Nazis. In the rough-and-ready labyrinths of social media, too, users clothed in anonymity have been reviving racist pseudoscience and conspiracy theories, without the fear of public censure or social ostracization.

And a significant cross-section of the population, especially in Eastern European countries like Hungary and Poland, have begun to reassert what they see as the fundamentally white and Christian character of their nations.

It is “an anti-Semitism that remains, that transforms, that reappears, that mutates,” observed Édouard Philippe, the French prime minister, as he and others grappled with the aftermath of Knoll’s murder last month.

Yet here, too, the specter of Islam has played a key if more oblique role. Many right-wing parties in Eastern Europe have been buoyed by their opposition to Muslim immigration, and the early sparks of white nationalism were defined by an antipathy toward Islam, scholars say.

In Britain, where anti-Semitic hate crimes have hit record highs in each of the past two years, such mutations have begun to ensnare the political left, adding another controversial layer to this evolving landscape of anti-Semitism.

With the confluence of so many different expressions of anti-Semitism, French Jews and others are once again feeling an “existential threat” to their place in their countries, just as generations had in decades past, says Rabbi Abraham Cooper, director of the global social action agenda at the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles.

“Until the 1990s, there were still survivors of the Holocaust, and France felt guilty about how it had treated Jews,” says Veronique Bencimon, a Hebrew teacher at a Paris high school, as she marches with thousands of others during last month’s Marche Blanche, or “silent march,” in honor of Knoll. “But now people feel freer to say things, and anti-Semitism has come to the surface again.”

“We feel insecure as Jews,” Ms. Bencimon says. “The state does not protect us enough.”

Nationalism and anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe

In the recent election in Hungary, neither a rival nor a policy platform was the focus of incumbent Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

Instead, in the weeks leading up to his landslide victory on April 8, in which his far-right Fidesz party also appears to have won a two-thirds supermajority in the Hungarian Parliament, Mr. Orbán focused on specter of George Soros, the Hungarian-American billionaire known for his philanthropy for liberal causes.

Plastered along the highway from Budapest to the airport, a campaign billboard displayed a looming picture of Mr. Soros, who with his Jewish family survived the Nazi occupation of Hungary before emigrating to England in 1947.

The billboard warned voters that Soros money would help dismantle the border fence Hungary built in 2015, at the height of the migrant crisis. And in an earlier campaign, posters featured Soros smiling, with the emblazoned words, “Don’t let George Soros have the last laugh.”

For many observers, this image was a direct allusion to Nazi propaganda, posters that depicted “the laughing Jew,” a trope cited often by Hitler. “The anti-Soros campaign is seen as anti-Jewish, even if not overtly,” says Borbala Kriza, a documentary producer gathering testimony from the remaining witnesses of the Holocaust in Hungary and elsewhere in Europe. “Soros was born before the war. He was persecuted in this country, and now he is 87 years old, and he is being persecuted again.”

Hungary currently ranks among the most anti-Semitic countries in Europe, according to the Anti-Defamation League’s global index. But many observers say the country has also begun to reject the traditional liberal ideals of a pluralistic democracy.

“This terrible division that exists, where we don’t accept the other as authentic, it worries me very much,” says Ferenc Raj, founding rabbi of Bet Orim, a reform synagogue in Budapest and one of hundreds of faith communities that can no longer call themselves “churches” under a 2012 law, rendering their assets vulnerable to confiscation by authorities. Rabbi Raj sees the problem as political rather than religious, as much a breakdown in tolerance and equality than a rise in ancient anti-Semitism.

And in both Hungary and Poland, right-wing lawmakers have worked to deemphasize or even erase their countries’ roles in the Holocaust. Earlier this year, Poland’s ruling Law and Justice party passed an “anti-defamation law,” making it a crime for any person in any part of the world to accuse “the Polish Nation” of complicity in Nazi war crimes.

In Hungary, Orbán unveiled plans for a new monument to the victims of the Nazi occupation in 1944. Protesters said the monument whitewashed the role that Hungarians played in the deportation of of more than 430,000 Jews, the vast majority who perished at Auschwitz.

“The message of the monument is simple and significant,” wrote Željka Oparnica, a scholar in Budapest criticizing the sculpture. “Hungarians could not resist Nazi Germany and, therefore, should be [absolved] of blame of the terrors of WWII.”

Hungary still grapples with ambivalence surrounding the labels of “perpetrator” and “victim,” says Gábor T. Szántó, a novelist and the editor-in-chief of the Jewish cultural and political magazine Szombat who deals with the theme in his narratives. “Our society’s biggest problem, beyond poverty, is a lack of empathy.”

Mutated anti-Zionism in Britain

When Jeremy Corbyn, head of Britain’s Labour Party, defended a politically-charged mural in East London six years ago, he probably had no idea his defense of a wall painting would ignite one of the most explosive scandals of his career.

He now says he was defending free speech when he endorsed the work, which depicted six stereotype-laden Jewish bankers playing Monopoly on the backs of the poor. But his party has since been hit with more scandals.

Some of his most fervent supporters have participated in Facebook groups in which members express violent and abusive anti-Semitic sentiments, praise Hitler, and threaten to kill Prime Minister Theresa May. Other Labour officials have shared posts denying the Holocaust, forcing some top leaders to resign.

At the end of March, nearly 1,500 protesters gathered outside Britain’s Parliament to protest Mr. Corbyn’s associations with people expressing anti-Semitic sentiments, and prominent Jewish donors to the party have stopped writing checks.

“In the United Kingdom, you already have a quiet exodus of younger Jews,” says Rabbi Cooper at the Simon Wiesenthal Center. “The traditional home for Jews in this socio-political setting was always Labour. And right now, the bottom has fallen out.”

As politics has become more polarized and vitriolic all around the Western world, the left’s deep antipathy towards Israel and its occupation of the Palestinian territories has morphed at times into full-scale anti-Semitism, critics say.

“Israel has become a pariah to the left,” says Mehnaz Afridi, head of the Holocaust, Genocide, and Interfaith Education Center at Manhattan College, a Catholic institution in New York. “In most Muslim views, Israel is understood as a colonial power, and Zionism is seen in a purely political frame.”

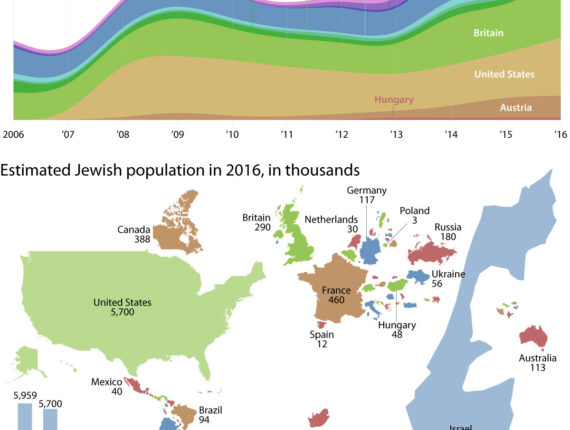

SOURCE: Anti-Defamation League; Executive Council of Australian Jews; Forum Against Antisemitism; Antisemitisme.be; Federation of the Jewish Communities in the Czech Republic; Mosaic Religious Community; French National Consultative Commission on Human Rights; Amadeu Antonio Foundation; Action and Protection Foundation; Observatory of Contemporary Anti-Jewish Prejudice; Information and Documentation Centre Israel; Community Security Trust | Jacob Turcotte and Rebecca Asoulin/Staff

An online incubator

In the United States, hundreds of tiki torch-wielding men chanted “Jews will not replace us” and openly displayed Nazi symbols at a “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Va., last August – even as the number of anti-Semitic incidents in the United States surged nearly 60 percent in 2017.

That was the largest single-year increase on record, according to a February report by The Anti-Defamation League (ADL), which noted that all 50 states saw an increase in anti-Semitic incidents for the first time in at least a decade.

“Charlottesville was definitely a tipping point, and definitely a wake-up call,” says Cooper.

But having launched a digital “report card” that surveys the amount of hate speech and terror-related content online more than two decades ago, Cooper continues to see the web as the most fertile space for spreading anti-Semitic ideas.

“The internet is a great incubator,” he says. “You can keep ‘The Protocols of Zion’ on life support, and there are new strategies and new languages, new ways to formulate old hatreds. And for the person who once upon a time would never think of saying anything this like this, the internet gives them a chance to express those views without any accountability whatsoever.”

“Remember the bad old days when you just spray painted a church or a synagogue or a mosque, and there was at least a chance that you’d get caught?” Cooper continues. “Today? Do whatever you want, and maybe, if places the Wiesenthal Center and others are doing their jobs, we can get a couple hundred thousand accounts suspended. Well, in a world in which Facebook has 1.5 billion, that’s just a drop in the bucket.”

‘We share a common fate’

Still, over the past year, even in the midst of one of the most significant surges in both anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim violence in the United States, Dr. Afridi has marveled at the corresponding surges in her own work to counteract it.

As a Muslim, she notes her unusual position as head of the Holocaust, Genocide, and Interfaith Education Center at a Catholic college like Manhattan. And as a scholar who analyzes the tangled intersections of religion and personal identity, she’s made it her ambitious goal to try “to eradicate anti-Semitism in the Muslim community,” she says.

In many ways, Afridi, author of “Shoah through Muslim Eyes,” has focused so much of her life to a typically Jewish cause because of her commitment to one of the most difficult of civic virtues in a liberal democracy: the value of sharing a common life together as equals, even amid the unavoidable human tensions that arise from difference.

Yet despite the growing sense of alarm that has followed the increasing number of anti-Semitic incidents in the US and Europe, there has been a new sense of purpose around the globe, she says.

“I believe what’s remarkable, as Jews are under attack, as Muslims are under attack, instead of segregating our two communities, it has galvanized us to recognize how we must be fighting for the other – and that is a very, very unique phenomenon,” says Rabbi Marc Schneier, who launched the Foundation for Ethnic Understanding in 1989 to help foster better relations between Muslims and Jews around the globe.

“Because we are both under attack, particularly from right wing extremists, we recognize that not only do we share a common faith as sons of Abraham, but we share a common fate,” says Rabbi Schneier. “Our single destiny must strengthen our bonds of concern, compassion, and caring for each other.”

• Staff writer Peter Ford contributed to this report from Paris.

Copyright © 2025 Foundation For Ethnic Understanding. All rights reserved. | Privacy Policy