Variety

By Andrew Barker

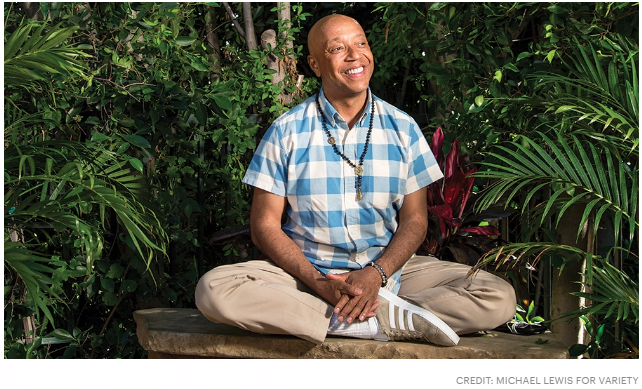

Variety’s Philanthropist of the Year carries Buddhist serenity to his struggle for rapid change in a world he sees in ‘perfect order’

Celebrity Activism.

Celebrity Activism.

It’s a phrase that rarely fails to raise hackles — and the specter of fashionable attachments to causes that accomplish more for the repute of the celebrity than the cause itself. But for multihyphenate mogul Russell Simmons, recognizing the power of his own celebrity was an essential step in his development into an activist and philanthropist.

“I think it’s a natural, slow process,” Simmons says. “I was always reading Scripture, and maybe when I was around 30 I started to pay more attention. I was about 35 when I started practicing yoga. It was back then when I started to realize that my voice mattered. I was more of a celebrity at 35 than I was at 30, and I started to feel the power of celebrity and how you can use it.”

Simmons’ direct invocation of his own celebrity is interesting, and he has little trouble recalling incidents in which celebrity endorsements had effects that were anything but superficial. For example, Simmons recalls an incident back in 2013 when he and a coalition of religious leaders, activists, and celebrities staged a rally and drafted a letter to combat harsh sentencing for nonviolent drug offenses.

“Justin Bieber tweeted about the prison industrial complex after we had our rally,” Simmons says. “And attorney general [Eric] Holder called our office right after…. We had already written a letter that was signed by everyone from Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie and Chalize Theron, to all these activists — Harry Belafonte, rabbis, imams — but it turned out it was Justin Bieber’s tweet that made it go pop.”

Criminal justice reform is but one of Simmons’ many causes, however this is a man who built a career out of intense multitasking. It’s how he gained the nickname “Rush” as a young man, a moniker that has stayed the same, save for the addition of “Uncle” at the beginning.

Criminal justice reform is but one of Simmons’ many causes, however this is a man who built a career out of intense multitasking. It’s how he gained the nickname “Rush” as a young man, a moniker that has stayed the same, save for the addition of “Uncle” at the beginning.

A hyperactive presence in New York’s early hip-hop scene, Simmons steered his brother’s band, Run DMC, to stardom, then co-founded hip-hop’s first blockbuster label, Def Jam, all the while dipping his toes into fashion, film, poetry, TV production, and digital ventures like Global Grind and All Def Digital.

And for the better part of the past two decades, the 58-year-old has applied the same sort of energy to his multifaceted philanthropic endeavors, which range from his namesake Rush Philanthropic Arts Foundation, which supports arts education in disadvantaged schools, to the Foundation for Ethnic Understanding, which he leads alongside Rabbi Marc Schneier to encourage greater communication between Jews and Muslims. He’s been organizing events and voter outreach programs through the Hip-Hop Action Summit Network for years now, and more recently started the Diamond Empowerment Fund to help reinvest jewel-industry profits into resources for diamond-producing regions.

Beyond that, Simmons has been active with groups like the David Lynch Foundation, which supports meditation in schools (Simmons is a vocal practitioner of Transcendental Meditation); PETA (he is an outspoken vegan); AIDS-support charity RED; and U.S. Doctors for Africa. More recently, Simmons’ focus has been increasingly drawn to the battles against police brutality and racial profiling, and he’s organized rallies and town halls in support of criminal justice reform.

Benjamin Crump, the lawyer and activist who represented the families of high-profile shooting victims Trayvon Martin and Tamir Rice, recalls Simmons volunteering not only to contribute financially to the Martin family after their son’s death at the hands of George Zimmerman, but also to act as a liaison between the family and the hip-hop community, who helped ensure that the issue remained at the forefront of social media.

“It’s easy to throw a couple dollars at something,” Crump says. “It’s harder to put your name and credibility on the line for an issue, and to say we’re not going to stop until we get some sense of justice or resolution.”

Crump also recalls that later, when he and members of the National Bar Assn., of which he is president, made a trip to Flint, Mich., to raise awareness about the contaminated water crisis, Simmons was one of the first to offer help.

“Russell made it his mission to go out there and get 2 million bottles of water to Flint,” he says, “and to put on these town-hall meetings that got people like the Kardashians, Snoop Dogg, and Jay Z involved with raising awareness about Flint. It was pretty deep, his level of commitment. I think I only gave him like 48 hours notice that some of the Bar Assn. lawyers and preachers were getting together, and ‘Hey, it would be good if you came.’ That’s pretty much all I told him, and he came.”

Simmons trumpets what he feels are the oft-overlooked contributions of leading hip-hop figures to social justice (“There’s not a rapper I know that gave away less money to charity than Donald Trump last year,” he quips), and notes that, thanks to his role as a hip-hop elder statesman, he finds it easy to work with younger activists in such groups as Black Lives Matter.

“I’m very fortunate that they still call me Uncle Rush and all that,” Simmons says. “Hip-hop is still cool, so [younger people] still fuck with me; I’m in a good position with them. And I’ll lead charges sometimes. But when I’m lucky, it’s me following them.”

Appropriately, Simmons says he’s happy to cede the role of leadership when he feels others are better equipped.

“I like to support other people’s work,” he says. “Whether it’s the Rush Foundation or the Diamond Empowerment Fund or the Foundation for Ethnic Understanding, or the work that we keep doing at the Hip-Hop Summit — all of that stuff is good, but helping people do better in their work is even better. Starting a foundation is oftentimes an effort that’s small. Unless you can scale and do a great job, then why not support someone else?”

Always outspoken and willing to reach across aisles, Simmons has often courted controversy, both as an entrepreneur and a philanthropist. His prepaid debit card line — RushCard — always walked a fine line between providing a service to factions of the urban community traditionally without access to banks, and being a clear profit-making enterprise. It came under particular fire when a glitch left some cardholders temporarily without access to their funds.

He is also upfront about having long considered Trump a friend (he feted Ivanka Trump during a fundraiser for the Diamond Empowerment Fund in 2012), though he quickly disavowed the substance of Trump’s presidential campaign, writing an open letter in 2015 titled, “To My Old Friend Donald Trump: Stop the Bullshit.”

“I have this thing where I try to see people in the best light,” says Simmons, who describes his politics as roughly agreeing “with everything Bernie Sanders says.” “I see where they have a blind spot, if I think they do, and I try to see where they have great humanity, if they do. And what do I know? … To me, it’s all about people doing the best they can as much as they can, and I don’t think there’s any contradiction to that. I don’t like to judge too heavy, ’cause if I start judging, how are people gonna judge me?”

By that same token, he takes pride in plunging headlong into ventures that more timid (or reasonable) figures might shy away from, a tendency that has helped produce some of his greatest successes.

Simmons acknowledges that the pace of activist causes can be slower than he’d like. Of the Rush Philanthropic Arts Foundation, which just last month raised $1.25 million at its annual Art for Life benefit, he says, “It’s not growing as fast as I’d like, but I hope that we’ll have a better year this year.” Yet it’s hard to deny the positive impact so many of his ventures have produced.

For Simmons, the most important of his accomplishments is his influence on the fight against the so-called Rockefeller drug laws in New York state, which saw Simmons meet with state legislators and Gov. George Pataki to push for an easing on harsh sentences for first-time drug offenders, enabling scores of inmates to apply for early release in 2004.

“When the Rockefeller drug laws changed, thousands of people came home from jail,” Simmons says. “And when I walk the street now, in the ’hood in New York, and people come up to me and say, ‘I’m home from jail because of you,’ that’s an amazing thing.”

Simmons acknowledges that the fight against police brutality that now occupies so much of his time will be a tough one — “This has been ongoing for 400 years, it’s not new” — but finds solace in his Buddhist faith that says the effort alone is worth the trouble.

“Everybody knows that all struggle is ongoing, and you can only do the best you can do. You work every day, then you sleep at night. We can’t expect anything to be solved, ever. Suffering is ongoing, lack of consciousness on some people’s part is always gonna be there. And your job is to do your part to lift people up and lift yourself up as part of that process.

“You have to accept that the world is in perfect order as it is, and you should do the best you can to play a part in bringing that perfection to a higher vibration. I can’t become hopeless, I just have to go to work.”

Copyright © 2025 Foundation For Ethnic Understanding. All rights reserved. | Privacy Policy